Welcome to the Virtual Opening of NATURE ABOUND

A Show of Paintings and Monotypes by ROB LICHT and CHRISTA WOLF

Join us for a glass of wine and a virtual toast while we take you on a stroll of our works throughout the winery’s tasting room.

View the show in person or virtually from August 1—October 31, 2020

Call ahead to make a reservation at

Leidenfrost Vineyards

5677 Rte. 414, Hector, NY 14841

607-546-2800

ABOUT THE SHOW:

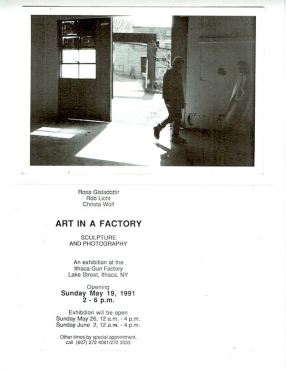

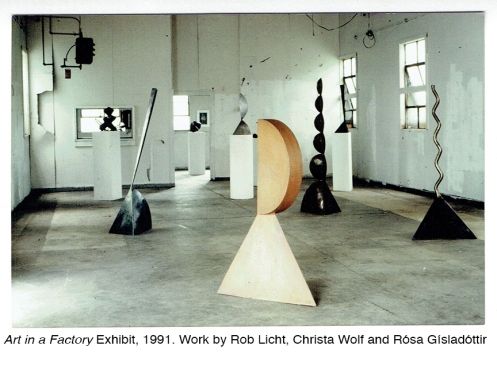

In 1991 Christa and I, along with Rósa Gísladóttir, organized a show at the Ithaca Gun Factory titled Art in the Factory. It was the last time the space was open to the public. Looking back over the years, it was one of my favorite shows. Even though our work was different–photographs by Christa, my steel sculptures , and large scale cardboard minimalist forms by Rósa– there was a palpable synergy between the work, enhanced by the raw vibrancy of the factory setting. Since then, my conversations with Christa always veer towards: “when are going to have another show?”.

In 1991 Christa and I, along with Rósa Gísladóttir, organized a show at the Ithaca Gun Factory titled Art in the Factory. It was the last time the space was open to the public. Looking back over the years, it was one of my favorite shows. Even though our work was different–photographs by Christa, my steel sculptures , and large scale cardboard minimalist forms by Rósa– there was a palpable synergy between the work, enhanced by the raw vibrancy of the factory setting. Since then, my conversations with Christa always veer towards: “when are going to have another show?”.

So, here we are, despite all that is going in the world, finally having that show. And it appears that our work has veered towards each other. Christa and I both draw inspiration directly from the landscape, I from this Eden of water and sky that has always been my home, and she from the green hills between the lakes that she now calls home, after settling here from Germany. Meanwhile, Rôsa returned to Iceland where she has had an illustrious career creating sculpture that draws upon the sparse landscape of her home.

Leidenfrost Vineyards, with its expansive view of Seneca Lake is a venue, like that first show, a wonderful enhancement of our work. It is softer and greener than the gritty factory reflecting how our work has become softer and more refined as we have mellowed over the years.

Social distancing rules preclude the celebration of an actual opening, but pour yourself a glass of wine and peruse the show from the safety of your couch. The winery is open on a restricted basis, please call ahead to make a reservation to see the show and enjoy a wine tasting: 607-546-2800.

VIRTUAL OPENING:

ABOUT ROB LICHT

Artist Statement: Nature Abound

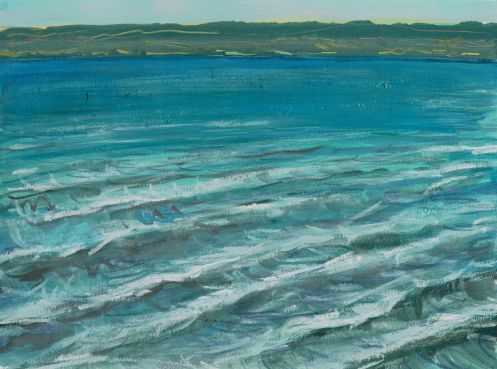

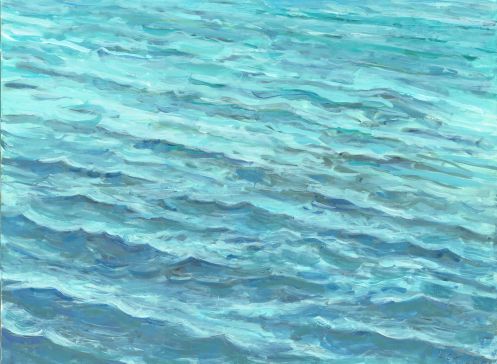

For those familiar with my art—sculptures and drawings that deal the influence of landscape on our lives—this show may seem like a departure from my more elaborate work . But the truth is, these small intimate paintings are a homecoming for me. Having grown up here, between the lakes, the land and the water were always the well from which my creative visions sprung. I have always done “plein air” painting, mostly as quick color sketches while on my forays into nature. For me, painting from nature is all about the process—immersing one’s self in the outdoors that is your subject, while you, yourself become the subject of whatever nature decides to throw at you. The scene is always fleeting, changing minute by minute, so that any attempts to capture the absolute must be abandoned; spontaneity must be embraced and working as quickly as possible leaves little time to mull over compositional choices. The effort becomes a trance-like meditation session, which is both relaxing and exhausting.

These paintings of the lake and the sky were done while staying on Cayuga Lake and other other water bodies. I use gouache because it dries quickly and the opacity allows me to build layers with out the fussy planning of watercolor. I prefer panel for the flatness of the surface, which I treat to hold the paint. These are sealed with a wax medium. I will also paint on paper or whatever else is at hand as I try to capture the elusive moments of sublime beauty.

List of Works PDF

Contact for Sales:

roblicht1[at]gmail.com / 607 342 0234

Please note that work is picked up or shipped after the show

or may be taken upon purchase.

Please add 8% NYS sales tax to listed prices.

Check, cash or PayPal to roblicht1[at]gmail.com

ABOUT CHRISTA WOLF

Artist Statement: Nature Abound

Living in the countryside overlooking the Valley of Seneca Lake I more and more feel connected to the plenitude of nature around me. I walk the hills, tend my garden, and worked the vineyards for some years. This leaves a vivid and everlasting impression with me that I recall in drawings and prints. These days I often work in water based media, painting and drawing on a wet media acetate that then can be transferred to paper with a printing press. This fluid technique allows the spontenaity of deep emotions ilicited by the of the natural world around me.

List of Works PDF

Contact for Sales:

christa.wolf44[at]gmail.com / 607 546 6654

Lately, my “day job” as a self-employed builder has distracted me from my creative time. Scheduling art into an already full schedule, at the end of an exhausting day, is difficult. The one exception is figure drawing, which is a practice I have tried to maintain, off and on, ever since art school. These are like scheduled appointments, with models and other artists or students, which I tend to keep.

I have been teaching figure drawing at the Community School of Music and Art, in Ithaca for several years. It’s satisfying because it is hard. As a teacher or a student there is always more to learn. I treat it as if it were a practice like Yoga; the point is not to end up with good drawings but to develop a habit of good drawing. When I teach, I refer to Eugen Herrigel’s short story, Zen and the Art of Archery where the master teaches his pupil that hitting the target is secondary to making a “right shot”. It’s an interesting pedagogical approach where good learning takes precedent over anticipated performance.

I also participate in model sessions, an age-old tradition where a group of artists sit around a nude model and draw. In this age of digital technology it is refreshing to do something in the same way it has been done for centuries. Except for the electric lights and music played on an i-phone, It is still the same dusty charcoal and smudgy pencil, and the models, aside from a tattoo here or there, could have walked out of the Renaissance. Stripped bare, we are all reduced to our basic humanity, timeless and universal.

In cataloging my drawings, which number in the thousands if you count all of the pages in my sketchbooks, I realize I have this whole body of work that has never been seen except by me. Even when I am having a good session and producing “right shots” only a few land squarely on the page; this is the norm, and editing is a part of the process. After a thorough culling, I have at least a hundred decent drawings. Why don’t I show these? Why do I consider this work an aside? Certainly, if you know my work with its sexualized organic forms and rolling seductive landscapes, you can see how figure drawing has informed my process. If drawing is the source, what better place for the viewer to drink?

You don’t see a lot of contemporary figure drawing and sculpture in galleries. Museums are full of old master figurative works but few shows are dedicated to current artist working in the vein. In the inner circles of the art world, figurative work is the exception, even though at one time it was central. One outlier is Jenny Sayville, whose luscious paintings of large women have set a recent record at Sotheby’s for a living artist.

Locally, I can’t think of one gallery that would show nude drawings. Unfortunately, in this sensitive age one has to tiptoe around the issue of nudity, especially when children may be present. I’m not talking Alberto Vargas pinups, but simply drawings that are inspired by the human form, something that everyone can relate to. Some refer to them as “nudes” while raising their eyebrows. I am inspired by the beauty of the models I draw, yet the beauty I seek is not any kind of sexualized stereotype. Each model has their own unique attributes that inspire me to draw. I prefer the female form for its (yes, I am objectifying- but with an artist’s eye) softer lines and less pronounced muscles, but robust males are interesting too. The pose is as important as the model but only some models really know how to pose (knowing yoga is a plus). As for any kind of eroticism, yes, it can be there, as it can be anywhere, but the truth is, if you are really drawing you are way too focused on capturing the complexity to even start down that path. Typically you have only five or ten minutes to capture it all. By design, the model session is an incredibly trusting and safe environment. In academic settings, as most model sessions are, any introduction of the erotic is absolutely forbidden. As an artist, it is a privilege to be able to study the body of another so closely, and one, that like a doctor, we treat with care and respect.

One thing that I love about drawing the figure, is that I have come to know our intricate inner workings. I teach superficial or artist anatomy: the parts we can see and how they relate to what is happening on the inside. When I look at a person, I can see the skeletal structure and muscles, I can see the flaws and perfections, the pain and the beauty that we all carry. I’ve had many x-rays and other imaging of my own body; these fascinate me like the medical anatomy books I pored over as a kid. I can talk specifics as I discuss my injuries to my doctors and physical therapist. It’s a visceral way of knowing myself.

I will share a few drawings I have done over the past few decades. They are remarkably consistent in showing my hand, which I think is good. By the names and dates scrawled on each I can remember specific sessions and models. Each captures a moment of concentration free from the distractions of life.

This past October, on a beautiful Saturday morning, I joined folks from The Backbone Ridge History Group on a walk following one of the original boundary lines from the Military Lots. This was an exciting opportunity for me as it ties into my own Boundaries Project, where I am exploring original lot lines from the division of the land as a means to compensate soldiers for their service in the Revolutionary War. Although I am exploring areas on state land near Dryden, I have deep roots in the Backbone Ridge area of Hector, having grown up nearby. Even though the federal lands are now collectively called Finger Lakes National Forest, locals tend to refer to it simply as Hector from when it was Hector Land Use Area. The mixed forests and grazing pastures at the apex of the gently curving arc of land between the two longest Finger Lakes is a patchwork quilt of squared parcels, a result of the government program of buying out ailing farmers during the great depression. There is a general agreement that the thin hilltop soils were fairly depleted and that, along with changes in modes of transportation, made it hard to compete with Midwestern farms. Some farmers decided to stick it out and many of their successors work those same lands today, thus the checkerboard of public and private land. Much of the forest is second growth, replanted by the forest service, who also removed much, but not all, of the evidence of the former farms. Because of this, there are more trees now then there were during the late nineteenth century when deforestation reached its peak.

Hector was my romping grounds as a kid, so I was excited to learn that the Backbone Ridge group shared my interest in the historic division of land into neat parcels. That division set into play the ensuing development of the land and helped establish the framework for the growing nation. My artwork explores how place helps define who we are; my feeling is that as much as the early settlers tried to alter the landscape to suit their needs, the landscape they discovered altered them and fed them in ways that they could not initially fathom. It certainly has had its effect on me.

Exploring these early boundaries, most of which are embedded in contemporary roads, hedgerows, and property lines, makes me think about what it was like for those early settlers to arrive at terra incognito and then to be faced with the heavy burden of improving the land by clearing timber, creating fields, houses, roads and mills. A step off any trail into the dense mixed hardwood forest gives one a sense of the overwhelming task. Initially, the forest must have seemed infinite; the incredible views we now enjoy from the open grazing land would not be apparent to them for years. The terrain was fairly gentle and accessible and punctuated by small streams that could provide waterpower. But as one left the ridge, these same streams must have proven to be obstacles as they funneled into steep east-west running gorges obstructing north-south travel. The upland soils today are thin and clayey, one wonders if that was always the case or if it is the result of overworking the land. The flat-bottomed valleys of glacial moraine would have been the most productive land then, as it is now. Granted a chunk of land through a lottery system, soldiers (or more likely, their heirs or subsequent speculators) likely had no idea of what they were getting into; new arrivals on the ridge must have cast a jealous eye towards those lowland parcels. After a century of farming, the thin hilltop soils became so depleted that the government stepped in and bought back much of the land, establishing the federal and state land preserves that we enjoy today.

If one traces the lineage of the families that ended up on the Ridge in the early 1800’s many of them still have family farms in the area and their names can be found on local road signs. Growing up here, it was understood that these are the hard working families that are the base of region’s agrarian economy. As hard as the work is today, I can only imagine what clearing the land with oxen and ax was like two hundred years ago. While our European counterparts were sipping tea and enjoying luxuries, early Americans were working their hands bare eking out a rudimentary existence in the woods. Yet this was part of Jefferson’s vision: A nation of independent yeoman farmers, self-sufficient, self governing, and hard working, but free from an oppressive government standing over them.

My walk with the Hector Ridge Backbone group was a planned outing to recreate the effort it took to survey just a small portion of the thousands of miles of boundary lines that were accurately surveyed under the leadership of Simeon De Witt at the beginning of the nineteenth century. We walked north along the Interloken Trail from Teeter Pond and then explored the northwest section of Military Lot 92, measuring a line south from Townsend road to a west- flowing stream and site of an old saw-mill listed as belonging to J.G. Skinner on a map from 1850. Along the way we encountered old cellar holes and foundations associated with the settlement. To measure the line we used an antique chain, which is both a unit of measure equal to 66 feet and the actual device used to measure it. It has 100 steel links, elegant brass handles at the ends and brass counters at set distances. The logic of the length has to do with the units of measure we inherited from the British. One acre is 10 square chains; 640 acres equals a square mile. One rod is a quarter of a chain, and was a common width for a road, such as in “One Rod Road”. Although it is not as simple as the metric system, there is some mathematical logic to it all. Since the roads bounding those early lots tend to form a mile square grid, and the Military lots were 600 acres, it isn’t clear what happened to the remaining 40 acres. Furthermore, A square mile, or 600 acres, can’t be evenly squared, thus the familiar rectangular parcels. Lots were divided into smaller parcels according to the soldier’s ranks, with a quarter of a quarter lot being the minimum standard of 40 acres that is still colloquially referred to (although that has more to do antebellum era in the South). The geometry of it all is pretty perplexing; it is amazing that the maps we use today still use those early lines as a base.

Having explored the concept of land division in my work for the past several years, it was really exciting to be using one those original devices. Albeit, we weren’t running through the brush, tugging on the brass hand-holds as I image the early surveyors did but, rather, given the antique nature of the chain, we gingerly carried it aloft of the pervasive mud with team of a dozen of us. Thinking back to those surveyors who forged through far worse and were guided only by compass, it is amazing to consider just how accurate they were. Flying over most of the country today, one can see the results of those efforts in the precise grid that defines the mid-west farmlands.

Our little Sunday jaunt opened a window to the past and to the incredible efforts it took for the early settlers to gain a foothold on this land. The work I have been doing raises questions about that dominion and the incongruity of the imposition of the grid onto an organic landscape with it’s own boundaries of streams, hills and lakes, and history of Iroquois settlement. Jefferson’s concept of the Yeoman Farmer was the incubator for the independent thinking American that we know today but also formed the mythos of the autonomous landholder that goes along with that. These early settlers had to make it on their own without depending on government support and that was the intended price of living free of government control. Here, in the hills of Central New York, whole communities of strong individuals developed from that history.

- The Failure of Communication, 2012-18

Speaking directly

In conversation and art it’s often difficult to say what you mean. We muddle through our words and leave the back door open so that rogue interpretations can slip in. We fear treading into the waters of deep sincerity because we might drown in an excess of emotion. As an artist, there is this constant question of how deep to go, how much vulnerability to reveal, how much truth to uncover.

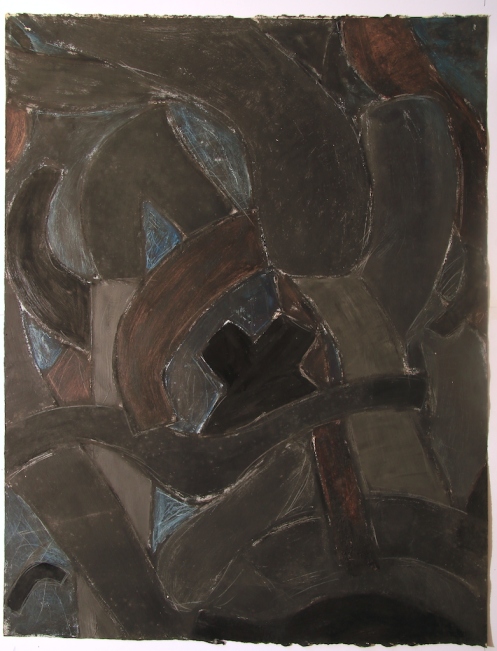

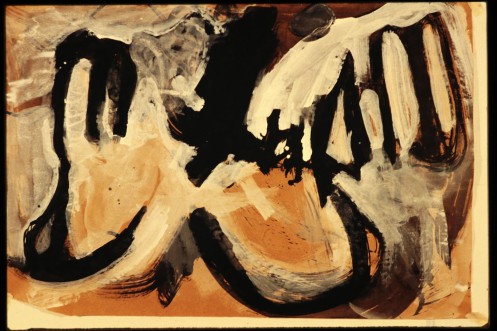

Recently, as I was transferring slides of old work into digital images, I had a fresh look at the art I created during a formative period—the time during and after grad school. Although I majored in sculpture, I was doing a lot of wildly expressive paintings on paper in addition to the requisite three- dimensional work. There was no shortage of emotional outflow in these images and a deliberate loosening of control over the medium. I used anything at hand; house paint, roofing tar, mud, and aluminum roof coat were typical. Many, in reverence to Ad Reinhart, pushed the boundaries of perceivable darkness. Some suggested impossibly dynamic sculptures. I worked on large sheets of acid-free kraft paper that a friend procured for me from the Cornell map library and did several each week.

Despite the prodigious outflow and boldness of the work, I was still muttering my way through expression. I didn’t know how or what I wanted to say. Like the loud drunk at a party, people were noticing me, but the substance of my expression was completely lost to all but my closest friends.

The art world is a place where fear of rejection, being a stranger to success, and expectations from others all steer us away from being honest in our work. Some artists appropriate styles and techniques based on popularity while others safely avoid introspection by embracing a practice that delves solely into formalist aesthetics or the concerns of representation. Sometimes I enjoy the process of working simply, taking all of my cues from the subject, such as when I do plein-air watercolors or figure drawings. Because these are not fettered with meaning, there is almost a Catholic guilt to how easy it is to make these.

Mostly, the work I am doing now, such as the recent photo-documentation of landscape interventions, has conceptual undertones and a specific message which might be tied to the history of a site or some other academic inquiry. I try to control the interpretation by establishing clear contexts which I elucidate in my statements and titles and reinforce by presenting the work as a series. The work is not wildly expressive like those older paintings, but based on ideas that originate outside of myself. The meaning is still a moving target and I do inject a bit self- reflection into the image making. The wild thrashing in my early work, like the way we all danced to Punk Rock bands, was a way to resist my own vulnerability; now, I’ve come to embrace my weaknesses and let it be an undercurrent in my work. The work is an open- case investigation that delves into the mysteries of our existence. As for answers, I’m open to suggestion; the goal is really to start a conversation, which is the first step to being understood.

Mixed media drawing 1985

- Drawing done at Cornell, 1986

Black painting, 1987

Graphite and paint on paper, 1987

Ink and paint on Kraft paper

Mixed media drawing 1986

The Glacier’s Receding 2015

As readers may recall, In 2012 I suffered a hand injury while working on a large outdoor sculpture. It wasn’t so bad I couldn’t do anything but the pain made working with wood and metal difficult and joyless. The injury became the catalyst for a shift in my practice: I steered my process towards one that embraced the ephemeral and consisted of actions or interventions in the landscape that I recorded with my camera. Although the hand has now healed and I am able to once again make objects, I began to question the need to do so. As a maker I have brought into being hundreds of sculptures, functional items, and building projects. Of the sculpture, about half has been sold or given away, and what remains, including a bevy of larger outdoor works, either sit in my yard or adorn my house, which has become my own private Merzbau. I have found homes for several large works, mostly loans to art parks, galleries or other public or semi-public spaces, but typically with no guarantee of security or maintenance. Moving and installing the larger work can take the better part of a day and I’m pretty good at moving these beasts, which weigh up to 500 pounds, but I get tired of dealing with these things on a repeated basis for little or no return.

Late in 2012 I had to yet again find a home for a piece—Steel Canoe— that I was actually pretty fond of but in terms of maintenance was difficult. It had been damaged at its last installation and was badly in need of refinishing. It was really an excellent piece that had been featured in several shows and cover photos and I thought someone would have bought it, but, for whatever reason, it never sold. I was living in an apartment at the time and had no yard of my own. So, embracing my new direction, I decided to turn it into a performance I titled: Scuttle.

Scuttle is word that typically refers to deliberate sinking of a vessel, usually in retreat, as in battle, and sometimes used to block a waterway. The deliberateness of the act is a way to reclaim power in a losing situation; rather than have your ship sunk, you sink it yourself in a controlled manner, with an option to reclaim it later.

I felt like I needed to retreat from this onslaught of heavy objects of my own making and to take control. With the help of my good friend Daniel and his sons, I floated Steel Canoe for one last time out into the icy November waters of Cayuga Lake (In a conceptual twist on the relationship between functional objects and art, it was a sculpture but also a fully functional, albeit, very heavy boat) and there, not far from shore, we sank it, with the cameras rolling.

The plan was simple but as things go when working in nature, there are elements you can’t control. First, It was seemed like it was opening day of some fishing season and boats were trolling back and forth incessantly. We wanted to be inconspicuous as a possible, but on the lake there are no bushes to hide behind so we had to wait and wait and wait and then work quickly. Second, sinking a vessel is a violent affair: at first the boat resisted my efforts to subdue it (I drilled holes in the bottom) and it needed a forceful assist; then, once the waters took hold, it rapidly succumbed to the deep with a final belching of trapped air that made it seem as it’s life was extinguished. It was all very violent. In the chaos, documentation was not what it should have been. The last part of the plan was sinking it in not so deep water where I typically swim so that I would see it resting peacefully on the bottom from time to time. This was the part of the action that included the possibility of retrieval; perhaps in a few years the zebra mussel-encrusted hull would take on new meaning and I could pull it out to display it anew. Yet, since that day, despite several attempts, I have never found it. It is lost to the mystery of the lake (or perhaps salvaged by some fisherman who saw it on his sonar).

I have stopped thinking about Steel Canoe and have even made more heavy sculptures since then, but recently I have been forced again to a full retreat from making big things. After 32 years of maintaining a fully functional studio/ workspace I am forced out of my current shop. The building will be razed to make way for a new medical center, leaving in its wake several small businesses scrambling. As I balance the financial burden of maintaining a shop with my needs as an artist, I realize that the schedule of work projects I do to make money so I can pay for the shop leaves me little time to make art. In this paradigm, the practice of making things becomes self-defeating; all of the effort to maintain the tools and workspace and to pay rent and overhead saps all of my creative energy needed to make artwork.

For now, most of the equipment is going into a storage unit. I will work small and ephemeral, draw and paint, and maybe do clay figure studies. I will get back to that creative space where the time and energy spent on preparing to create, doesn’t overwhelm the creative act. I am going to embrace this new period in my career and make the best of it. I am scuttling the shop but this time I won’t lose the key.

Like most metal workers, I have a love-hate relationship with steel. It is heavy, dirty and loud to work with. Welding involves all kinds of hazards and assaults to the body: burns, cuts, and metal slivers, the fumes of welding and the dust from the resin-bonded grinding disc. I have tinnitus from years of grinding metal and a piece of titanium in my wrist, surgically implanted after a drilling accident. In the winter, my shop is freezing and it’s a constant battle between turning the fan on or conserving what heat there is.

Oh, yes, I wear safety gear—when I can stand it: safety glasses, ear protectors, welding helmet, face shield, respirator and an assortment of gloves. It’s a constant on-off-on-off and not everything is compatible; hearing protectors don’t fit under a welding helmet, respirators fog up the safety glasses, and gloves make certain fine task impossible. None of it is comfortable.

So, at times, I hate what I love. Like yesterday when my task was to clean the mill scale off of a 1,000 pounds of mild steel for a new sculpture in my Landforms series. Mill scale is a hard, black crust on the steel that comes from the heating and cooling of the production process. It actually protects it for a while but is a poor surface to paint over and, thus has to be removed. It is so hard that it resists sanding and it has to be sand blasted or removed with acid. I don’t have a blasting set-up so I am stuck the latter.

Steel is a poorly understood material. Everyone knows it is hard and strong but what they probably don’t know is that its strength comes from its malleability. It bends before it breaks and it can easily be persuaded to take on new forms. The most misunderstood aspect is the oxidation process. Oxidation, like combustion, is the combination of oxygen with the fuel material, in this case iron. Usually it is slow, but with enough heat and a jet of oxygen, the steel actually burns—which is how torch cutting works. So, while steel is strong and versatile, it also has this transient quality; when metal work leaves the shop, the goal is to have some permanent coating on it so that it doesn’t rust away, but, left alone, it will go through an organic transformation with moments of beauty so fleeting that few of us get to fully appreciate it.

To remove the mill scale I wash it with acid (a process that involves a kiddy-pool). In doing so I expose the soft underbelly of the plates and get to witness this instant transformation of the patina. There are subtle greens, magentas and yellows, like a color-field painting. Once I rinse the metal, it instantly starts to burn with soft orange haze of rust. It is hard to describe and harder to photograph. It is at this point that I wish I could hold it, but I can’t. Sometimes I try by using a wax finish, but for outdoor works in public display, a slowly rusting finish just doesn’t fly. People want control and permanence. They expect steel to hold fast against the elements and for surface to be predictable. They will never see the soft, delicate, fleeting surface of the steel that I love.

Hour after hour, day after day, I have been sitting and watching the lake as it cycles through its endless moods. The light constantly changes, the wind shifts, and the waves rise and fall. My observations start before sunrise, when an orange thread first appears over the hills to east, and go into darkness, when all of the man-made lights compete with the lights in the night sky. When the wind is still and the lake is mirror-smooth, the town of Aurora, three and a half miles across, looks like a dollhouse collection set on the hills. When the wind kicks up white caps and the waves pound the shore, the lake becomes an ominous beast. The waves are not huge by ocean standards, but, in contrast to the scale of the landscape, they have a power that demands respect. Boats caught in the white caps struggle against the irregular rhythm and can be heard surging through the churning water. Swimming or canoeing becomes out of the question.

Hour after hour, day after day, I have been sitting and watching the lake as it cycles through its endless moods. The light constantly changes, the wind shifts, and the waves rise and fall. My observations start before sunrise, when an orange thread first appears over the hills to east, and go into darkness, when all of the man-made lights compete with the lights in the night sky. When the wind is still and the lake is mirror-smooth, the town of Aurora, three and a half miles across, looks like a dollhouse collection set on the hills. When the wind kicks up white caps and the waves pound the shore, the lake becomes an ominous beast. The waves are not huge by ocean standards, but, in contrast to the scale of the landscape, they have a power that demands respect. Boats caught in the white caps struggle against the irregular rhythm and can be heard surging through the churning water. Swimming or canoeing becomes out of the question.

The direction of the waves works with the sun to create infinite patterns of color and light. Shifting currents can make the water a pea soup, so opaque one day that I can’t see my hands when I swim, and, then, clear as a cup of green tea the next, revealing a forest of weeds and fish before the bottom drops away to milky-bluish depths. From where I sit, the lake is over three hundred feet deep in the center—modest by ocean standards but deep enough to hold it’s mysteries.

During my stay at the lake house, I took hundreds of photos of the lake, trying to record every mood, every nuance. A moment frozen in time cannot capture the noisy energy of waves; videos and painting seem better suited. I am trying to figure out the visual pattern that allows us to read them as waves. There are layers of color, light, shadow and reflection. The pattern repeats but is never the same. Quick, expressive marks capture the energy but gloss over the intricate lace-like reflections that a more careful study will reveal. I suspect that any one approach will fail and that the only way to know the lake is to study it thru a multiplicity of experiences and to employ equally diverse means of expression. Perhaps I will need poetry and dance to fully explain all that I come to learn.

When something presents a seemingly simple surface, but under scrutiny reveals an intriguing depth and complexity, I get drawn in. Like swimmer on a hot summer’s day, I am ready for the plunge.

For longer than I can remember, the lake has been central to my life. To any one local to the area “the lake” refers to Cayuga, that beautiful long glacial trough filled with glistening blue-green water. Although we rarely speak it’s full name in direct reference, every local business, event, and organization possible borrows the moniker. The name originates in the people who made this area home for centuries before they were brutally unseated by Sullivan. His charge, from General Washington, was to make way for settlement by the revolutionary soldiers who would later come and establish themselves in the neat one-mile-square boxes that were imposed upon the rolling terrain.

For longer than I can remember, the lake has been central to my life. To any one local to the area “the lake” refers to Cayuga, that beautiful long glacial trough filled with glistening blue-green water. Although we rarely speak it’s full name in direct reference, every local business, event, and organization possible borrows the moniker. The name originates in the people who made this area home for centuries before they were brutally unseated by Sullivan. His charge, from General Washington, was to make way for settlement by the revolutionary soldiers who would later come and establish themselves in the neat one-mile-square boxes that were imposed upon the rolling terrain.

In the view from space, the Finger Lakes are easy to discern; Cayuga, the longest, would be the index finger. By referencing the adjacent lakes, towns are easy to find but hard to get to since one must travel around each finger to travel east and west. Ferries, which at one time were deemed essential, haven’t plied these waters in a century. Roads, which often follow the grid that Simeon DeWitt, the Surveyor General of New York, devised as a means to divide and distribute the land, have names that give a hint to the ancestry of those early settlers: McCulloch, MacDougall, Allen, Skinner, Yarnell, Swick, and so on. The townships themselves, in a quirk of history, were given classical Greek and Roman names by Robert Harpur, a clerk in DeWitt’s office who preferred the poetic to the pragmatic simplicity of numbers: Ovid, Romulus, Ulysses…There are eleven or twelve Finger Lakes in all, depending on who is counting. It is fitting that the names of seven of the lakes pay homage to the original inhabitants: Cayuga, Seneca, Keuka, Canandaigua, Owasco, and Otisco. Ignoring all of the lake houses, docks and other incursions on the shore, the long bodies of water are the landscape features that would be most recognizable to a Haudenosaunee from five centuries ago. The lakes are the most dominant feature and, more than anything else, define the region and its inhabitants.

As I ponder these thoughts about the lake, I am sitting on a lake-house deck overlooking the water. The soft crashing of the waves on the worn flat stones is the sound track to my ruminations. Some people around here own lake houses; everyone else who grew up here, in the land between the lakes, has dreamed about them: either renting one for a week or two, owning a little summer cottage, or having a full blown year-round house on the water. Until now, I have never realized this dream. Through fortunate circumstance, I have two weeks to spend idly staring at the water and forgetting about work and a heap of other obligations.

My mother grew up connected to the water on the North Shore of Long Island. She instilled in us a love for the water, taking us to the lake when we were younger. She always dreamed about getting back into sailing, which she did with great proficiency in her youth. In 1965, my parents bought 10 acres, not on the water, but across the highway from it. The modernist house my father designed would have sweeping views up the lake from the third floor balcony. My father lost his job, the first of many layoffs, and the dream deflated like a kid’s party balloon left lingering on the living room ceiling until it simply fell back to the floor, where it was left unnoticed, unmentioned, forgotten.

I have never lost the dream and have kept my eye on lakefront properties, but, as the region has boomed in popularity, lakefront prices have swelled to the point of impossibility. Cottages used to be simple, unadorned, summer havens owned by locals, but, they are now becoming the exclusive retreats of wealthy imports. Locals would offset their tax burden by renting weekly during the warm season (most cottages were not winterized), but the new arrivals mostly keep their newly restored lake “cottages” to themselves. Thus, access to the lake for the common working folk, aside from a few parks, is becoming harder and harder. To finally spend two solid weeks, without interruption, at the lake, after 55 years of contemplation, is a dream come true for me.

When I was a little kid I was told I was going to be an artist. Paintbrushes, pencils and drawing pads were thrust my way. By the time I was in grade school I was known as the class artist. I drew Snoopy for other kids and, at home, drew copies of nude women from art books. The embers of my father’s burning desire to be an artist, something he too felt as a child, were reignited in the possibility that I would pursue the career he sidetracked to become an architect, a more practical choice.

So, I went to art school. First, to New Paltz State, and then, after dismissing the lack of seriousness in my partying classmates, on to a real art school: The Maine College of Art. My parents were legally bankrupt; I paid for school entirely myself by working summers as a billboard painter. After getting my BFA, I went to Cornell for my MFA, working as teaching assistant and a house painter to pay the bills. Although some of my classmates and friends came from incredibly wealthy families, none of that rubbed off on me. In fact, I usually paid the bar tab. After school I continued to work in the trades doing blue collar work: ornamental plaster, house painting and carpentry, until I got a part time teaching gig at Ithaca College. But that didn’t pay very much either. After 12 years, my position was dissolved in an acidic dispute over equality and pay, so, I went back to the trades where I still work today.

During this entire period I have kept up my studio practice: I’ve had shows, won awards and residencies and been invited to speak. I am continuously making new work that explores how art is essential to sifting out meaning in this complex and chaotic world. Now, more than ever I feel my work is on the verge of something, that my sifting is producing more nuggets of gold and less dross. Although my practice has dramatically shifted, I am getting to the core of what I have been searching for my whole life. It’s not drawing Snoopy, but, then again, I’m sure Charles Schultz was an early influence .

I’m writing this as I should be writing yet another statement of intent for yet another grant application. This, at a time when I should be heading towards bed to be rested for yet another day of hard work. It goes on like this, month after month , year after year, trying to get recognition, a few crumbs of funding, or a foot in the door so that maybe, one day, I won’t have to lift my hammer to pay the bills. So that I won’t have juggle art and survival.

I keep track of who wins grants, or gets major shows or opportunities and increasingly I’ve become wearily aware that most are people with the means to be an artist- people with money, support and connections. Artist who don’t have to work full time to survive, who have the time and money to not only make art, but to go places, see things, and meet the right people. I start to wonder: “can I afford to be an artist? or, should I just throw in the towel?”

Unfortunately, this digression will not meet the requirements for the letter of intent I need to write tonight. Nor, is it 2500 characters or less. If do I get this $3,000 grant, it may buy me a few weeks of blissful creativity- but, not if I don’t apply.

“What are you doing?”

That’s a typical question I get from bystanders when I am out in the woods trying to make my art. Today, an acquaintance asked about the long rope I had over my shoulder as I headed out to a favorite isolated creek. “I don’t know,” I told her. “Really?” she insisted. “really, no clue”.

I typically work alone so I can avoid questions like this. Making art is a rather private affair, and I feel stifled when I know someone is looking over my shoulder. It’s hard, in ten words or less, to explain my entire process.

The truth is, when I am being truly creative, I don’t want to know what I am doing. I want to be open the situation at hand, listen to the site and follow my gut. It’s almost the opposite of when I show up at a job site, where each stage of construction is carefully planned and the outcome is established long before we start. Sure, I’m going to bring some tools and materials- such as the last minute decision to grab that rope; the same rope that I salvaged from Nova Scotia while making art there; the rope, that when wet, as it would be by the end of the day, stinks like the bottom of the ocean. What I take is only a guess as to what I’ll use. Planning, while essential for some aspects of my practice, is the death knell of creative genesis.

When I was a kid, loner that I was, I’d sneak off and head to the creek behind our ten acres on the edge of town. There, I’d engage in all kinds of projects: making damns, diverting water, catching crayfish and taking an inventory of aquatic life. It was my world. Like most kids, my world was distinct from the world of my parents. My typical response to queries about what I had been doing: “nuthin”. It was not so much that I was trying to be secretive, I just knew that there was no way in hell they’d understand the importance of what I was doing. I guess that way of working, of exploring and playing in the woods and creeks, hasn’t really changed. For me, making art is all about getting back to that kid mind.

The interesting thing about my little exchange in the parking lot was, that I learned that the preserve was in the process of expanding it’s boundaries and that surveyors had just been there, flagging trees to mark the invisible boundaries. This ties into recent work I have doing which explores how boundary lines and the parceling of the landscape have helped define our relationship to the land.

The only difference between what I do now and what I did as kid, is that, now, I try to weave meaning into my actions. I take into account the history, geography and ecology of a place and try to make sense out of how human activity intersects with the natural. I come home and write about it and pour over my documentary photographs and try to make an exhibition. I try to figure out what the hell I really am doing. And then (and only then), I share it with the world.

![IMG_4858[web] IMG_4858[web]](https://roblichtblog.files.wordpress.com/2020/08/img_4858web.jpg?w=161&resize=161%2C161&h=161#038;h=161&crop=1)